There’s a pivotal scene in The Doors, Oliver Stone’s 1991 biographical film about the American rock band of the same name. The very young Jim Morrison was taking a road trip with his family and came upon an accident involving an overturned truck and an injured Native American Indian bleeding on the side of the road. When Morrison publicly recounted the incident later in life, the story had morphed from one Indian injured on the side of the road to several Indians scattered all over dawn’s highway, bleeding and dying. And then later to, “One of the Indians soul’s leapt into my own.” Whether this significant shift was manufactured by the singer or whether it was merely his own memories morphing and expanding over time is unknown. What isn’t in doubt was the extent to which he was traumatised by the experience and somehow personalised it to the point where it became a central narrative in his life from that day forward. People often look back at traumatic events in younger life as an emotional catalyst for change.

It’s Saturday 13th May 1989. I’m awakened sharply by the incessant ringing of the telephone in another room. It invades the late stage of a glorious dream involving Davie Cooper dribbling through the holes in a massive Curly-Wurly and has continued beyond the tenth conscious ring. It’s still dark outside, and the sense of dread when receiving a call outside of normal waking hours builds rapidly in the twenty or so steps from duvet to device. There’s still enough time for my fevered imagination to draw lines through the names of relatives before the high-pitched voice of Al – a mate from work – punctures the doom.

‘Are ye up?’ he asks, pointlessly.

‘Jesus, it’s five in the mornin’, man!’ I remind him.

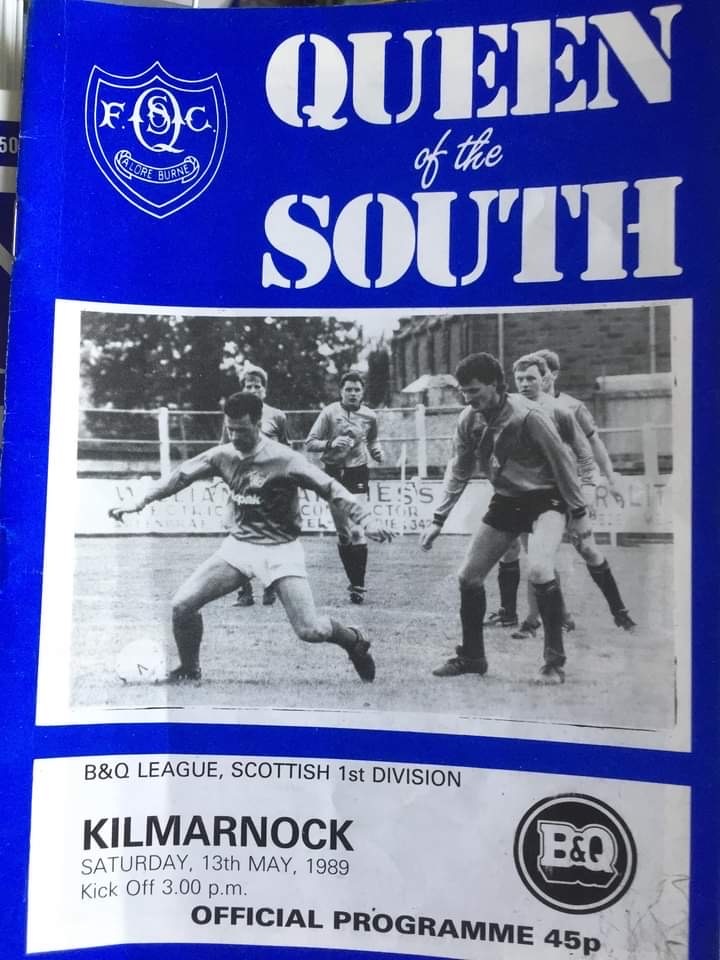

Al is a Kilmarnock supporter; a die-hard. This particular Saturday is likely to be a traumatic one for him, his club and the substantial band of supporters who’ll later travel south to Dumfries for the final game of a hugely disappointing season against already relegated Queen of the South. And since he knows I’m not a Killie fan, and therefore ambivalent about their fortunes, it’s not a call I had expected. Nor welcomed. ‘Ma da’s no’ the best,’ he confides. I’m starting to join the dots. Al and his brother need a lift down the A76. I’m presumably their best bet. My own team have already won the league title; the top division one. A meaningless home game against Aberdeen doesn’t tempt. And there’s something about Al’s desperate pleading that brings out the Good Samaritan in me.

Meanwhile, in another part of the region, Willie Watters is also awake. He hasn’t slept well. He too isn’t looking forward to the match. The Killie striker isn’t expecting to play a part in today’s vital game at Palmerston. Willie has been dropped for the games leading up this one and wasn’t even stripped for last week’s 3-2 defeat to Clydebank at Kilbowie Park. It’s been a frustrating season all round. As usual, the strikers bear the brunt of the criticism for the lack of goals. 41 goals scored in 38 games would be phenomenal for a single player, but not for an entire team. It’s the 60 against that has led Kilmarnock to this precipice, though. The arithmetic is simple: win today by five clear goals and pray that Clyde don’t beat a St. Johnstone team already safe from relegation and dreaming of the beaches. Willie Watters is a local hero with a knack of scoring goals at will. He knows that – given the chance, given the jersey – he could live up to his side of this unfeasible bargain. He just doesn’t expect it will happen.

Seven days earlier, Kilmarnock superfan, Sandy Armour trudged disconsolately away from another debilitating defeat suspecting, perhaps even expecting, that Scotland’s oldest club – his lifelong passion – were on the verge of going down to the lowest tier in Scottish football. The days following a bad loss are arguably toughest on the fans. The players and management begin to focus on the next match. The pain remains, no doubt but the promise of a successful ninety minutes ahead is being drilled into them from the first minute of training in preparation for it. The fans only have the hope, and famously, it’s usually that which kills. Sandy’s week of countdown began with him drowning out the pain in The Howard; a session that gave birth to a momentous hangover as he headed to work on the Monday.

Sandy anticipated five long days of relentless banter from his Glaswegian colleagues. Best to find a quiet desk, soothe the fevered brow, try to find any glimmers of positivity from a woeful decade in which Killie’s part-timers have clung on for grim death. But Sandy’s week is about to get much worse. A phone call from his mate Alex reminds him that, although it seldom feels like it, there are more important things in life than football. Alex’s mum has passed away suddenly. A second call twenty-four hours later confirms that the funeral is being held at the chapel in Whiteinch on Saturday morning; the day of Killie’s final dance with the devil. Head in hands, Sandy Armour contemplates the synchronicity.

Saturday comes around. It’s just after 10am and a mini-bus heads south-west from East Ayrshire. On board are twelve beleaguered Kilmarnock disciples. ‘Killie ‘til I die!’ they defiantly sing, already envisaging singing it en route to more dilapidated grounds often surrounded by hedges from August onwards. The group comprises ten adults, one of whom is my brother-in-law, George Kenney, and two youngsters; Steven Cree and his brother, Derek. A planned stop takes in the Thornhill Inn, The Buccleuch and The Queensbury Arms; the adults gaining sustenance from pints and predictions shared with hundreds of other nervous pub-goers. Steven and Derek busy themselves with repetitive circuits of the bakers and sweet shops on the village’s main street; a rite of passage for all fitba-kids endured while waiting for a Da or uncle to emerge from the pre-match pub ritual. Bellies full, the caravan of hope snakes its way south.

Dougie Reid’s white Vauxhall Nova brakes as it approaches the slow-moving line of supporters buses. He chides himself for not having left his hometown half an hour earlier. The radio is on, his mate scouring the airwaves for anything that hints at Jim Fleeting’s team selection for the most important match in the club’s recent history. There’s nothing though. A mix of poor reception on the rural, tree-bound parts of the A76, and the broadcaster’s pre-occupation with the Old Firm makes his search a fruitless one. The pair’s nervous anxiety grows as Dumfries draws closer.

My own journey, chauffeuring two equally fraught diehards, started half an hour later than Dougie’s. I find their palpitations funny. Even though I have nothing invested, I goad them mercilessly, as if was an Honest Man. It’s the price they have to pay for my service behind the wheel. Just beyond Mauchline, we spot an accident. It doesn’t look serious and no-one involved appears to be injured. It’s a scorching hot day, and that won’t be helping tempers which, as we pass carefully, look destined to become frayed. I watch in the rear-view mirror, and just before we reach a bend that will take them out of sight, I see one protagonist strike another.

Twenty minutes further on and the traffic slows. A queue forms. My passengers drum nail-bitten fingers. We might not make it to the ground in time for kick-off. It’s another accident. The A76 has more unexpected narrow bends and dangerous twists than an Elmore Leonard novel but still, two accidents on the same stretch of road within minutes of each other is being to feel – as Jim Morrison would no doubt describe it – portentous. The second accident involves a farm vehicle and a lorry-load of chickens. Some look like they will be on their way to Bernard Mathews sooner than perhaps planned. My comrades are now convinced a form of voodoo is at work.

Like his idol, Willie Watters, Sandy Armour has managed about twenty-three minutes of sleep during a stiflingly hot Friday night. He wakes but eats little in the way of a sustaining breakfast. Over his lucky Ben Sherman boxers, Sandy wears the black; the regulation sombre-suited attire of the mourner in the days before a more celebratory attitude to a life well-lived calls for colour. He heads north, in the opposite direction to his moral compass. This will be the first full catholic funeral mass that Sandy has attended. Twenty minutes in and it’s clear he has underestimated the time that the ceremony will take. Sandy Armour is now another in an increasing line of desperate men convinced that they won’t be where they should be come 3pm on Saturday 13th May 1989. He permits a thought that it might be for the best to ruminate before giving it the two-footed tackle it deserves. It’s definitely not the time to be thinking like an Ayr United fan, he concludes. He shakes Alex’s hand as he leaves the chapel. Alex smiles, wishes his mate well before finding humour, as all true Glaswegians do, in the bleakest of circumstances

‘Haw, big man. Ah’d keep the black tie on if ah was you!’ he advises, prophetically.

Sandy Armour’s silver Cavalier speeds, bullet-like towards Dumfries. It passes through New Cumnock, Sanquhar and Thornhill leaving a hazy blur of exhaust fumes and small boys wondering if Doc Brown’s De Lorean has just buzzed their towns. Eventually he catches up with the raggle-taggle convoys of buses, cars, vans and motorbikes that comprises the Killie travelling support. And a handful of impartial observers such as your narrator.

Jim Fleeting hands Willie Watters a starting shirt. It feels like a last throw of the dice. But the striker has a pedigree. He has a decent ratio of goals scored at Hamilton, Clyde and St. Johnstone before arriving at Killie. He’s a striker who knows it only takes a fortunate one going in off the arse to turn around a drought. They cross the line, they all count. Against all the odds, Willie feels like this could be the day the dam bursts.

George Kenney, Steven Cree, Dougie Reid and Al, my work-mate, are all similarly delighted to see Willie Watters take the field as 3pm approaches. Sandy Armour finally reaches the ground later than most and the sight of the striker warming up immediately lifts his spirits. He is convinced multiple speeding fines might await but for now he’d take that punishment in exchange for a glimpse into an unlikely future that has Kilmarnock FC playing in the First Division for at least one more season.

‘Fuck sake, man … yer jinxin’ us,’ Sandy hears coming from supporters grouped together in the tiny corrugated enclosure opposite the main stand. They regard his doleful demeanour. He removes the tie. It’s the least he can do.

You could throw a decent-sized fishing net around all of us, the faithful majority and the unfaithful few. The protagonists in this tale stand only feet apart such is the desire for shade offered by the small, rusting canopy. The game starts and I immediately feel like one of them. There’s something about a group of males – for it is predominantly men and boys in evidence – coalescing into a single amorphous wave of fervent supportive yearning that catches even the casual observer off guard. I feel more involved here in this tiny wriggly-tin shed than I’ve often felt seated in the gods at Ibrox, weirdly enough.

The wingers and full backs are touch-tight to the nearside fans. The referee’s been every shade of religion known to the West of Scotland in a tense opening quarter. The linesman hears every abusive profanity yelled in his direction, especially during the proliferation of early flags that catch Willie Watters on the wrong side of the last defender.

But Queens are a beaten side, relegated already and offering the resistance of a club resigned to their fate and desperate to put a desperate campaign behind them. It’s no surprise when they concede. The Killie fans around me are relieved. It’s been coming and there’s plenty of time for more. The amount of transistor radios being lifted to ears increases dramatically. Willie Watters scores a second, the type of sclaffed effort that Gary Lineker specialises in. He wheels away, ball in hand. Through the glare of the Dumfries sunshine, he briefly looks like a heavier silhouette of the Barcelona striker.

Three more goals flash in rapidly; two more for Watters and one for Robert Reilly. The cowshed feels and sounds like it will take off from its rusty baseplates. Clyde and St. Johnstone are deadlocked, whilst Killie – and Watters in particular – are suddenly playing football like The Harlem Globetrotters play basketball; looking like they’ll score every time the ball goes into the Queens penalty box. The ebullient striker has another one in the net, but the lino’s flag is raised. He’s peering into the sun but rules it out for offside in any case. The striker is convinced he was onside but doesn’t argue too much. These goals are like Glasgow Corporation buses; he senses there’ll be another one along in a couple of minutes.

Unlike Willie Watters, the Killie fans are growing restless. Having had unlikely dreams of salvation validated, Queen of the South are now enjoying some sustained pressure which is force the visitors back. A long punt out of defence sees Watters anticipating and breaking free, bearing down on the advancing Queens keeper. Neither blessed with natural pace, they both go for it in apparent slow motion. Then they both bottle it. The ball rolls free and, reacting first, Willie Watters puts it in the empty net. He heads for the fans, ‘aeroplane-ing’ alongside the low metal rail that encloses them. He high-fives – or slaps – the entire front row as the remainder pogo their way up and down the shallow concrete steps.

The final whistle blows and immediately we are, to a man and boy, on the Palmerston pitch. I went to a football match for a day out in the sun, not particularly caring who won or lost, and end up as part of a pitch invasion. We think it’s all over; it isn’t quite. They’re still playing at Clyde, the elderly and more wizened remind us. But Killie have won 6-0. And Willie Watters scored five of them! ‘The impossible dream’, Al keeps saying, over and over. There are tears in his eyes. He reaches into a jacket pocket and deftly pulls out a small pen knife. It makes me consider whether carrying it is a premediated act, or whether it is always with him. He reaches down and cuts two decent-sized squares of the worn triumphal turf. One for him and one for me. I find the gesture touching and troubling in equal measure.

Players have been swamped. Sweaty jerseys are being wafted by bare-chested fans. It’s hard to know which ones have been prised from Kilmarnock’s heroes. The fans are being drawn magnetically to the main stand. I see a man at the front, dressed predominantly in black, like one of the Blues Brothers. He seems deliriously happy. I see my brother-in-law amidst a group of men I know to be his mates. Two youngsters are on shoulders, their arms dancing and waving scarves. This is what real happiness looks like; a thick broth of joy, anticipation, relief and regret that connects everyone involved in a last-day escape from the desolation of relegation. A victorious encore will surely happen. Even the parsimonious cabal of local butchers and accountants who constitute the board of Directors are temporarily free of criticism. A lone player emerges. It’s Killie defender, Davie McFarlane. His name rises high above the throng. He climbs onto the wooden rail that surrounds the Palmerston directors box. He dances. He waves. He catches a scarf and twirls it high above his head. Like my father, and his father before him, I’ve followed Rangers all my life, but I briefly wonder if I’m only now understanding that this is what being a football supporter is all about. And then I and everyone else in the ground begin to realise that it absolutely is.

Shocked faces, tuned into the frequencies, tell the story before it is fully known. A desultory tannoy announcement confirms it. In the last game of the season, Clyde have scored from a hotly disputed penalty so far into injury-time that it almost constitutes a pre-season friendly. All realise immediately what it means, but still mouth ‘so what does that mean?’ to each other; hoping that some incomprehensible law of physics will reverse the inevitable. But it won’t. Killie have been relegated. Despite recording the biggest away score-line of the entire season. Despite keeping a clean sheet for almost the first time that season. Despite Willie Watters scoring five legitimate goals and a sixth that had its claim for legitimacy cruelly taken away from it. Killie were down. For Sandy Armour, George Kenney, Steven Cree, Dougie Reid, Al and hundreds of others … and yes, perhaps even me … it feels like the world has just ended. Dougie ties his precious scarf, the one that commemorated his team’s historic League triumph in 1965 and the Scottish Cup win of 1920, onto the Palmerston goalpost, and leaves it there.

Willie Watters makes his own way back north. He has the match ball with him, but it means little at the moment. He listens to pundits dissecting the last-day outcomes and hears, depressingly, that those watching at Firhill had no idea where the seven minutes of injury time came from. He sees the litter of discarded scarves and Killie paraphernalia that track the route back to Kilmarnock painting a poignant picture of failure.

But it offers a release of frustration that, for the real supporter, is always temporary. ‘We’re goin’ down, we’re goin’ down,’ sing the still-defiant ones returning on George Kenney’s minibus. Next season will be different but they’ll still all be there, older and arguably wiser; rain, sleet or shine, home and away. They’ll spend this forever-damned.

Saturday night – and most of the following fortnight – consoling themselves before emerging with renewed hope. A determination to see the relegation as a spring-board to better things. A necessary clearing of the dead-wood that often happens when the status quo has to change.

And so it proves. The first months of the new season will witness a rejuvenated team, led from the front with characteristic flair by new signing, Tommy Burns. They will be promotion challengers right from the start. They’ll play the type of football that space, time and better quality allows. And before 1989 ends, fans’ favourite Bobby Fleeting will have taken over control of the club.

Steven Cree, now a hugely respected and successful film actor, looks back at the game as the point where his love affair with Kilmarnock FC was cemented. ‘Although painful at the time, it was the springboard to a brilliant season that ended very differently on the last day with promotion at Cowdenbeath. Palmerston was a turning point for Killie.’

As then, George Kenney remains in banking (and he is still my brother-in-law). ‘Looking back, going down was a good thing. That season in the Second Division was great. I didn’t miss a game, home or away, except Tommy Burns debut at East Fife which doesn’t count in any case as it was abandoned mid-match due to a snowstorm which prevented me from getting any further than Newton Mearns.’

Willie Watters still enjoys cult-hero status at Rugby Park. When he hung up his boots in 2000, he’d scored over 175 league goals for twelve different clubs. ‘During that long summer in ’89, I desperately needed a break. Had to get away from it all. I went on holiday to Tenerife, only to bump into Colin McGlashan. It was his late penalty for Clyde that put us down.’

The current Leader of East Ayrshire Council, Dougie Reid recalls being at a party held in Glen Barrowman’s house in Edinburgh. ‘It was just before the famous 0-0 draw against Hibs at Easter Road where we held onto our Premier League status. I saw this scarf in Glen’s room and said ‘that’s a rare old scarf. I had one just like it once.’ Glen said, ‘it is yours. I untied it from the post, and I’ve had it ever since.’ He offered to give me it back, but I told him to keep it. It had obviously been luckier for him than it had been for me in the twenty years previously.’

Sandy Armour is a Kilmarnock FC legend. No-one embodies the grit and determination necessary to be a life-long supporter of a provincial club quite like Sandy. ‘That day in Dumfries will live forever in the memory of the Killie fans who went to the game but in hindsight, it may well have been the best thing to have happened. Had we stayed up, the old board could have remained, the ‘Fleeting Revolution’ might never have taken place and who knows where we’d be today. As it stands, we got back to the top division in 1993 and have remained there since. I do love a story with a happy ending.’

I lost touch with workmate Al shortly after getting a new job in Glasgow. I still support Rangers, but then again, I’m most certainly fickler than the other stars of this story. So, for those of you considering the notion, forget ‘A Shot At Glory’ or any other equally implausible shite. Here’s your movie!